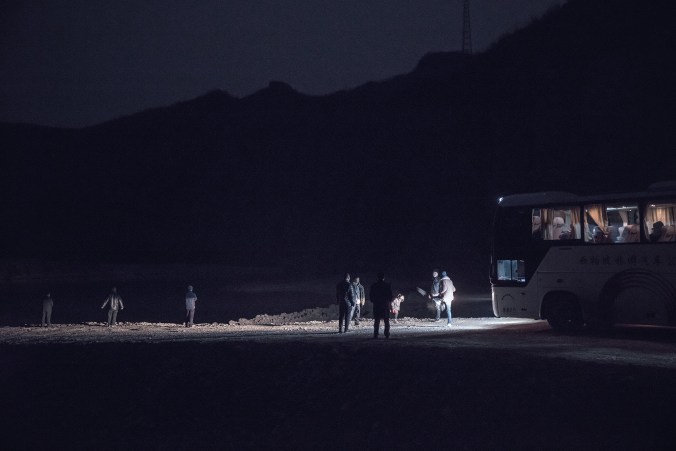

15 – Mountains May Depart – Jia Zhang-Ke – 2015 – China

Here we have another film that serves as a placeholder for a filmmaker’s entire decade of output. The 2010’s, for me, at times can best be defined by the effect that seeing the films of Jia Zhang-Ke has had on me. I have mentioned once earlier about my infatuation with “Taiwanese New Cinema” and this is by way of the films of Jia. I struggled to choose a favourite from Jia’s 2010 output. While A Touch of Sin was my entry point and Ash is Purest White may be his best film of the decade, for me Mountains May Depart was the one that hit hardest. Maybe it’s the epic narrative that spans 26 years starting in 1999. Perhaps it is the look at the effects of globalization through the lens of the emotional distance for the members of a family. Here is a film that fails somewhat in it’s ambition, yet touches me to my core. Why? Because I’m a sucker for movies where people dance.

Many of the themes explored in Mountains May Depart will be familiar to viewers of Jia’s other work. Language barriers, familial estrangement and the erosion of a culture through time and corruption. Many of these themes will show up again as my list continues. Culture and borders has become a large aspect of my life this decade. I met my wife in 2012 and from that moment language became a huge aspect of my life. Cultural barriers and race was present where they weren’t necessarily, before. Shino is from Japan and through getting to know her, living with her family and learning her language and her culture, my entire perspective shifted. Suddenly more than ever before, distance was a constant hurdle in my life. At times because of visa regulations, we lived in separate countries, at times we’ve been in the same room and have had no way to effectively communicate. I see culture, now as a daily aspect of my life, an experience I gain so much from.

Mountains May Depart explores a similar relationship in the form of a mother and her estranged son. Their cultures and world view are so divergent, but we are left with the hope that this gap could eventually be closed. Jia doesn’t go so far as to show that moment happening, but in stead chooses to revisit the opening shot of the film where the protagonist Tao (Played by the director’s wife and constant collaborator Zhao Tao) dances to the Pet Shop Boy’s “Go West.” The image of her, now an elderly woman, full of life’s regrets, weeping and dancing in the snow in front of an ancient pagoda smashes through decades worth of cultural barriers. I was personally shattered.

14 – Moonlight – Barry Jenkins – 2016 – USA

Here is the only film of the decade to win the Oscar for Best Picture that will appear on this list. I generally go into the awards season full of apprehension as all my favourite films are crushed by the same overwrought trash from the same overplayed directors. It didn’t go down the way that Best Picture’s usually do (and should) and in spite of the way the scandal affected Moonlight’s time in the spotlight, the reversal of the Best Picture from La La Land to Moonlight is the most enjoyable moment I’ve ever had watching an awards ceremony. If you have access to the video that was shot that night at my friend’s Oscar party, where in real time the award was given, taken away and finally placed in the rightful hands of Barry Jenkins and co, then you know just how happy I was.

All that bullshit aside, I was devastated by Moonlight on first viewing. The structure was the first thing that struck me. Three defining moments at very different times in a young man’s life. There is an inevitability to much of the film. A sense that this cannot end well. As the boy grows up in impossible surroundings and tries to deal with and accept himself as somebody who does not and cannot fit in, it starts to feel like a happy ending is out of reach. I found the film’s final act to be both a touching, soft look at those barriers breaking, but also a sad realization that it will take more than one choice, one experience to break through the conditioning that comes with being a man in a man’s world.

I have had conversations with a friend who did not find this film to go where it needed to go in terms of it’s intimacy. He expressed feeling hurt by the film’s fear of male sexuality and the treatment of the gay experience. I appreciate his point of view, but for me I didn’t see this film so much as being about homosexuality. Though that was a large theme, I think it was partly used to express something about toxic masculinity and the cycle of violence that it produces, particularly in the African American population. I saw Little as a tragic product of his environment. Not taught enough how to love, taught too often how to fight. That we don’t get to see him completely blossom is not necessarily a flaw, because what does happen opens the door to an entire universe of possibility without having to pin it down to one moment or one experience. I left Moonlight feeling thankful for my loving, accepting family and the open, caring environment that I’ve been lucky enough to live in.

13 – Phoenix – Christian Petzold – 2014 – Germany

I have trouble talking about how much I love Phoenix without mentioning the way it ends. I actually don’t know a huge amount of people who have had the chance to see this film, so I will continue to refrain from doing so, other than to say that this film lands on perhaps the most perfect note of any film this decade. I sat dumbfounded as what I already knew to be true was laid out before me in such a powerful and elegant manner and as the credits rolled, I found myself completely paralyzed. This feeling has never fully gone away.

Phoenix follows Nelly (Nina Hoss), a Jewish lounge singer who survives Auschwitz and returns to Berlin and receives facial reconstruction surgery to repair a gunshot wound. The doctor is unable to make her look the same as she used to, but she is otherwise very beautiful. She reunites with her husband, who does not recognize her, but sees a similarity in her to his supposed late wife. Her husband convinces her to pretend to be his late wife (Herself… I hope I’m not confusing this too much) so that she can collect a large inheritance owed to her.

Petzold excels at this type of historical, cross-genre dramas. His work with Hoss has produced many lovely films and Phoenix may be their strongest collaboration. He has a certain knack of effortlessly playing out the twisty, turny plot with all it’s secrets and reveals and never losing a string or letting the main objective get out of sight. When he finally ties the whole thing up, it’s a delicate, powerful moment of silence, rather than a bang that left me doubled over in emotion.

12 – Good Time – Josh and Benny Safdie – 2017 – USA

Alright, let’s get crazy.

If you haven’t seen Good Time and I’ve told you that you should, then what the hell are you waiting for. If you haven’t seen Good Time and I haven’t told you to, then now you’ve been served, get the fuck out there and watch this crazy movie. If not for yourself, then for me.

This aptly named thriller from the Safdie Brothers is a non-stop ride through the chaos of one man’s night on the streets of New York City trying to break his developmentally disabled brother out of jail. There is an energy to this film that bores it’s way into your brain. The buzzing score (Oneohtrix Point Never) and jarring camera work give a sickening feeling of unease and Robert Pattinson’s best performance to date helps to ground this madness, while keeping you riding the edge of your seat.

Fun. Non-stop craziness. There’s a plastic bottle full of liquid LSD, introduced in the best cinematic tangent I’ve ever seen. Good Time is the best example of a low stakes thriller. This kind of slacker cinema usually comes with lazy visuals and a half cooked plot. The Safdie Brothers Never. Let. Up. Good Time is a shot of adrenaline straight to your heart. Good Time isn’t about right or wrong. It is a frenetic nightmare odyssey through New York City that refuses to slow down. When the end finally comes, it lands with such a beautiful and thoughtful grace note, that I can’t help but feel compelled to start the movie again as soon as the credits finish rolling.

11 – Mad Max: Fury Road – 2015 – USA-Australia

It’s very rare that a film that forgoes emotional depth for visceral thrills wins me over. More often than not I find myself yawning at spectacle films, checking my watch and counting the minutes till the obvious signals that it’s about to end. It’s not that I hate big budgets or special effects, but more often than not they serve to distance me as a viewer, rather than bring me in on the action. Mad Max: Fury Road is the antidote to that problem.

I saw this in an empty theater in Japan with my wife and mother in law. We sat in the third row, but my mother in law chose to sit near the back. I had heard the hype at this point, of course, but had no relationship with the original trilogy of films and was admittedly skeptical. There are times where my skepticism completely poisons a viewing experience, even minutes in, but minutes into Fury Road I had already been slapped upside the head and halfway down my row so many times, I couldn’t count. My wife asked me to stop screaming at the screen. There wasn’t anybody in the theatre, so I didn’t see what the big deal was, but I swear I did my best to stay quiet. Luckily the low end in the soundtrack washed out my constant excited giggling.

Pure visual storytelling. A keen spatial sense. Constant reinvention and a self awareness and understanding of genre trappings and how to subvert expectations. Mad Max: Fury Road is a master class in action film making. This movie will be the bible for the next generation of action directors. The stunts, the effects, the sound all serve the plot and sequencing of the movie.

I’m not gonna lie. This movie is a big silly mess when you break it down into parts. It’s all kinds of too much and as we go through the second half of this list, you’ll really start to see a theme of “Less is More” Before this decade I was much more inclined to feel that I couldn’t get enough “More” and as I progress through my 30’s and find new things to appreciate in life, I’m noticing that I get much more out of the minutiae of every day than I do a balls to the wall thrill ride. Mad Max walks around like it has something important to say and I think the message is mostly empty and dumb, but I appreciate that it doesn’t waste more than a few percent of it’s screen time trying to say it and rather focuses it’s time doing what it does best. High octane and tons of fun without lowering itself for the sake of appeal. I would go to the big box theaters much more often if the marquee movies were more like this.